ESSAY: connect with new audiences

Good Bye Party, Walker Art Center January 18th, 1969

Photographer Unknown

In the late sixties, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis commissioned a new building from architect Edward Larrabee Barnes. The old building was razed and curators scrambled to insert art into found spaces within the community. They improvised using abandoned warehouses (this was the sixties, before warehouses had winebars), old vaudeville stages, shopping centers, bridges, streets and even the city lakes. Although the current history page on the WAC site skips over this legendary period, this was a time of enormous excitement, both for the art itself, blooming politically and experimentally, and for the community.

The walls came down, and the city rushed in, ushering in the era of the “museum without walls.” (The phrase has its origins in Andre Malraux’s 1947 book, Le Musée Imaginaire, which introduced the notion of cultural experiences that transcend the confines of real estate.) At the Goodbye Party on January 18th, 1969, members adorned the walls, devoid of the previous precious art collection, with improvised graffiti—signaling a new urban relationship.

It is critical to understanding this period that outreach, although most certainly achieved, was unintentional and thus undocumented. According to Martin Friedman, the musuem’s director, there was no mandate or even much interest in reaching new audiences. Rather, the emphasis was on maintaining existing staff, membership and identity during the transition. The primary focus was the new building: working with the architects, designing spaces for upcoming shows and events, and planning for the opening.

The museum offices were moved from the original building in bucolic Loring Park to a seedy section of Hennepin Avenue in downtown Minneapolis, a zone characterized by “adult” rather than art venues. Although work in the new offices began with an emphasis on existing programs, the surroundings resulted in a significant shift of perspective. Mildred Friedman, Design Curator and editor of WAC’s design publication, Design Quarterly, defines the moment of transition, “Because we were downtown, we began to be interested in what was going on downtown; we became interested in the city itself.” Thus the museum began to branch out into the city with new programs and publications relating specifically to the civic life of downtown.

The performing arts program, under the direction of Suzanne Weil, brought programs to dozens of new venues through out the city, and a seminal show (sponsored by the Minnesota State Arts Council, but influenced by WAC’s director and curators) Nine Artists / Nine Spaces, challenged artists to produce public work, with highly charged results. All of these efforts brought substantial new audiences in contact with not only the traditional holdings of a modern art museum, but highly innovative new commissioned works.

The lack of exhibition space didn’t hinder the exhibition schedule and Walker Art Center mounted two major shows, 14 Sculptors: The Industrial Edge and Figures in Environments in the unlikely venue Dayton’s, the local department store in downtown Minneapolis. The Dayton-Hudson Corporation held a major role in the civic and philanthropic life of Minneapolis and shared board members with the museum. Its flagship store anchored the vibrant pedestrian Nicollet Mall which had been designed by Lawrence Halprin and Associates. The store had a large, general use auditorium that was used for everything from end-of-the-year white sales, pet and garden expositions, visits to Santa, pop music concerts, and fashion shows including a 1967 visit from Twiggy.

Regardless of the setting, both shows were groundbreaking exhibitions; 14 Sculptors: The Industrial Edge(1969) was a important minimalist show that was one of the first such exhibitions in the midwest, introducing works of Sol Le Witt and Donald Judd. It was a phenomenon, one of the first expositions to display art made from industrial materials and processes. Figures in Environments (1970) presented novel approaches to the human form and included works by Alex Katz, George Segal and Red Grooms. Grooms enlisted art students and families to help him construct Discount Store, an enormous 3D paper maché construction, termed a “picto-sculpturama.” The sculptural store-within-a-store was a nod to the first discount store, the recently opened Target, also owned by the Dayton Corporation. The juxtaposition of industrial materials and industry, sculptural human figures and fashion manikins increased exposure to both; shoppers wandered among sculpture, art patrons among the merchandise.

Several special issues of Design Quarterly resulted from the relocation to downtown. As noted above, the museum began to take an interest in their immediate environs and assemble writing and criticism on the subject. The first was DQ77, Projects for Urban Spaces chronicling the urban landscape. In DQ78/79, a special double issue, the uncelebrated Hennepin Avenue shared equal billing and consideration with the heady conceptual architecture of Peter Eisenman and Ant Farm. With DQ80 Making the City Observable, and DQ86/87, The Invisible City, DQ forged a relationship with urban mapmaker Richard Saul Wurman and began organizing symposiums on the urban environment, both local and global. All of these efforts contributed to a heightened awareness of the importance of the role of the museum in addressing the city.

This era also marked a steep increase for the performing arts program at Walker Art Center. In 1968, not long before the move downtown, Walker Art Center spun off its young Center Opera Company from its modest program of jazz, folk and chamber music concerts and named Suzanne Weil as performing arts curator. Despite the lack of auditorium or venue, or perhaps because of it, the program expanded from two to three dozen events a year to over two hundred. Working throughout the city, Weil introduced a vibrant series of performing arts into the far reaches of the city, bringing new life into abandoned buildings, parks, civic spaces and organizations.

Weil built new relationships with a number of existing arts organizations gaining use of their stages by co-sponsoring events. Weil explains, “I learned early on that if I used someone else’s space for one of our events, I’d have to pay rent. But, if I sponsored something with them, I didn’t have to pay rent, so I worked with The Shubert Club, The Thursday Musical and The Minnesota Orchestra. What could be more different from WAC than The Shubert Club? Bruce Carlson, a very smart person there, was intrigued with the notion of presenting new work, so we did a series of new music concerts titled, “Nobody’s Old Favorites and My Six Year Old Can Paint Better Than That Concert.” The series, which included works by Lucio Berio and Cathy Berberian, drew a mixture of members from both organizations and sparked interest and publicity for both.

Weil also co-sponsored events with the Park Board, notably using both the parks and the cities renowned lakes; one series included concerts where the musicians were on rafts and the audience was on shore, and the reverse where the musicians were on shore and the audience were in canoes. Public events, the concerts were accessible, even if not from a privileged position on lake or shore, to anyone who happened to be lakeside. These co-sponsorships began an era of cross-fertilization; by sharing venues, calendars mailing lists, they introduced new patrons to the reciprocal institution.

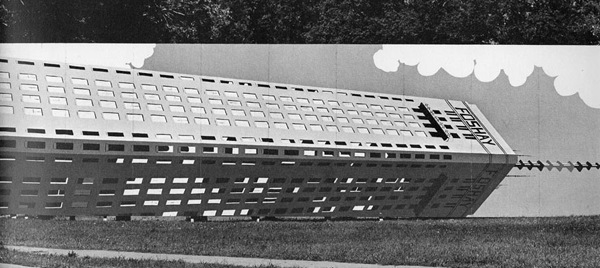

Weil also began a program of artist’s residencies, dancers and composers coming to the city for long periods of time to create commissioned work. These created the opportunity for sustained relationships with local artists and performing arts groups which continued long past the residency. Preparation for these pieces began months before the residencies with a scouting trip for the artist to explore the city for potential performance and rehearsal space. Viola Farber performed in the IDS Center a business and shopping center in downtown Minneapolis, a hub for the Twin Cities famous network of Skyways. Yvonne Rainer and The Grand Union and Trisha Brown Dance Companies performed in the parks, even using the ponds. Twyla Tharp chose the St. Paul Civic Auditorium. For one month, anyone could come and watch her create the piece, one minute per day. Modern dance was not the usual slate of events for the Civic Center, a fact underscored by the sign hanging in front that read:

According to Weil, “The Golden Glove Boxers watched modern dance, the dancers walked through the boat show,” providing an unlikely mix of subject and audience for modern art.

During this same period, the Minnesota States Arts Council initiated an exhibition of public artworks, 9 Artists / 9 Spaces, Although not sponsored by Walker Art Center, it meshed with the Musuem’s presence in the local environment. Martin Friedman, Walker’s director, served as an advisor to the effort and Richard Koshalek, then WAC’s Assistant Curator, was loaned as project director. The show, initially named “Sculpture in the Cities,” was conceived as a vehicle, “to take art works outside the relatively elitist confines of the museum and put them into the pathways and parks of the mainstream public.”

The Minnesota State Arts Council was explicitly addressing the notion of art and the public, and in undertaking this show, had looked to the 1967 New York exhibition, Sculpture in the Environment. Sponsored by the New York City Administration of Recreation and Public Affairs. Both shows were rooted in the 1966 National Endowment for the Arts Works in Public Places Program, “to accustom the public, particularly those who might never visit a museum or gallery, to the sight and impact of the works of contemporary sculptors.”

Koshalek, who was trained as an architect, used the opportunity to expand the nature of environmental art, challenging the artists to choose sites and create site specific work “that they had always wanted to do but were never able to, even artworks considered impossible.” Koshalek didn’t invite the artists to park their artworks in public space, he called for radical innovation on the part of the artist. The name of the show was changed from Sculpture in the Cities to 9 Artists / 9 Spaces in an acknowledgement that the work was developing outside the boundaries of traditional sculpture. It also belied a more fundamental shift of emphasis from the public towards the art itself. Koshalek’s primary concern was the artist; the show wasn’t conceived as an opportunity for the non-elite to see art, it was an opportunity for the artists to further their own artistic trajectories.

The public aspect of the show spectacularly backfired when, one by one, each piece fell victim to controversy or mishap. Koshalek remarks, “It was the show that nobody ever saw. Not even me, and I organized it. I never saw it.” The show was designed to be innovative, and the Arts Council was prepared for limited controversy, but was unprepared for the wholesale demise of the show. The leap from the sanctioned environs of a modern art museum to the great (public) outdoors, resulted in a host of unexpected misunderstandings and confrontations. Controversy related to a specific artwork, within a museum (at least at the time) stayed neatly in the art world. Controversy on the street proved harder to contain.

Koshalek states, “Museums consider themselves public, but only a few thousand belong to them.” The public, in the form of law enforcement, neighborhoods, landlords, politicians, and even people living in a park, reacted.

9 ARTISTS / 9 SPACES

The show’s demise began before it even opened. Ron Brautigan proposed a piece threading a quarter mile of galvanized steel tubing through Fair Oaks park. This was 1970 and the park was inhabited by “the people” (described in the catalogue as, “restless young people gaily bedecked with long hair and beads,” who informed the artist that it was “a people’s park” and that it belonged to them. Brautigan countered that, “he was people, the sculpture was for the people” but, before the night was over, the piece had been vandalized beyond repair.

8 ARTISTS / 8 SPACES

Fred Escher proposed to pick an abandoned house in a St. Paul neighborhood damaged by riots and fire and symbolically revive it by lighting it with an extravagant amount of neon. He stated, “I want to take this burnt out area and I want to fill it with neon, light it up and give it new life.” On opening night, as the house was blazing with 200 lbs of neon, Koshalek recalls hearing two men behind him saying, “…that’s the building where we’ve stashed all of the explosives in the basement…” He continues, “I’m not sure what I’m hearing, but it was a time just after the city riots and fires and the city was jittery, so I go to my car, drive to a pay phone and call the police. I try to explain that we’re hosting a public artwork and I’ve overheard that the building with our sculpture is filled with explosives. The police arrive and…. it’s true! They find tons of explosives in the basement. So, of all the buildings we could pick in St. Paul, we picked the one that was stuffed with dynamite! The building became a crime scene, the entire thing was shut down.”

7 ARTISTS / 7 SPACES

Meanwhile, William Wegman proposed a billboard with an image of Minneapolis’s iconic skyscraper, The Foshay Tower, on its side. It was a straightforward depiction, painted from a black and white photo of the building – horizontal rather than vertical. It went up on opening night. In the middle of the night. University officials had neglected to inform University Police and, the police, edgy from recent bomb activity in St. Paul, contacted the FBI. The FBI showed up at Koshelek’s office the next morning to inform him that they’d read it as a bomb threat and dismantled it. Nobody (associated with the show) ever saw it.

William Wegman, What Goes Up Must Come Down 1970

acrylic on wood, 10′ X 35′ University of Minnesota, West Bank Campus, Minneapolis Artists 9 Spaces, 1970 Minnesota State Arts Council, photographs by Eric Sutherland

6 ARTISTS / 6 SPACES

Siah Armijani had built a series of “bridges to nowhere” and proposed to simply plant a pine tree and build a bridge over the tree. He planted the tree and built the bridge. Possibly a harbinger of things to come, the day before the opening, the tree turned brown and died. Undeterred, the exhibition crew went out and purchased every can of evergreen spray paint they could find and gamely attempted to conceal the true state of the tree. It was of no avail, on the day of the opening with everyone assembled in front of it, the bridge fell over. It collapsed in front of the crowd like a performance piece or, as Siah described it, laughing uncontrollably, “an act of God.” It collapsed, it was meant to be. Or not be.

5 ARTISTS / 5 SPACES

Richard Triber had a strong interest early on in saving the environment and proposed to build a piece, over one story tall, of refuse and brush collected from the garbage department. It was placed in front of the capitol building to call attention to ecology and waste. Before the scaffolding was covered with brush, some thought it was a scaffold for a hanging. Once the brush was added, the Governor declared it a fire hazard and, despite the fact that it was a state funded artwork, had it removed.

4 ARTISTS / 4 SPACES

Robert Cumming proposed to build a sculpture out of letters and sentence diagrams from all of this correspondence with the Arts Council. He built a huge set of scaffolding to hold these sculptural sentence diagrams, including over 1150 painted alphabet forms, on a vacant lot near University Avenue. Walker Art Center’s photographer, Eric Sutherland was photographing it when a semi-truck driving down University Avenue, lost control (perhaps distracted by the work?) and crashed into the site, destroying the piece and, incidentally, destroying Eric Sutherland’s camera and extended record of the work. It was a total accident, unpredictable, and the piece was gone.

Robert Cumming, Sentence Structures 1970

painted wood, 1150 alphabet forms, each 12″

University Avenue and Prior Avenue, St. Paul

9 Artists / 9 Spaces, 1970 Minnesota State Arts Council, photographs by Eric Sutherland

3 ARTISTS / 3 SPACES

Although the show’s catalogue states, “Barry Le Va’s work out in Prior Lake was the safest since few could find it, and few tried,” the piece almost landed Richard Koshalek in jail. Koshalek recounts, “Barry wanted to do a piece in the countryside, so I rented a helicopter to scout locations and we found a site near Prior Lake. We landed the helicopter and a fellow staggered out of a trailer, drunk as can be. We did our best to explain to him that we wanted to build a piece of art there. The fellow said, “Sure, you can build a hotel for all I care,” Le Va built his piece, a series of concrete stepped platforms, in the countryside. However, Le Va, concerned with the formal aspects of scale, perspective and vista in nature, ignored the formal nature of private property. After the piece was completed, a sheriff showed up at WAC with a warrant for Koshalek’s arrest; the drunk fellow in the trailer had no authority to grant access and the owner of the land, a farmer, had damaged his farm equipment on the concrete platforms. The piece was removed, Koshalek managed to stay out of jail.

2 ARTISTS / 2 SPACES

I don’t have accounts of what, if anything, befell the last two artworks, by Allan Erdmann and Judson Nelson, but the show provided a wake up call to those who would venture to place art in public spaces and alerted curators to the unintentional potential for confrontation. Undeterred, Richard Koshalek went on to direct the visual arts program of the National Endowment for the Arts, placing an unprecedented amount of public art in throughout the United States.

Thus, despite the lack of a physical space, WAC not only maintined, but actually increased the institution’s visibility. The citywide events gathered huge anticipation for the new building, beyond the original patrons from Loring Park. The opening was an event and the building became a destination that reached out to a more general population than the previous membership. Once the new building was built, and the shows returned to galleries and programs returned to their theaters—the museum didn’t retreat fully into its white walls—but expanded into the park with the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden, one of the largest urban sculpture gardens in the country; eleven acres with forty permanent artworks and changing exhibitions.

While the effect on individual citizens and artists exposed to WAC’s programs during this period is impossible to assess, Minneapolis, during this time, developed and maintained a vibrant commercial gallery scene, reflecting new interest and enthusiasm for modern art. Dean Swanson, Chief Curator at that time, points out that a strong contemporary art institution increases support to artists by way of collection and patronage.

How is this recounting of an obscure, almost forgotten era in Minneapolis relevant to Organizations Across the Region hoping to Connect with New Audiences in 2008? There are several factors that make it unlike the present. Walker Art Center was free to the public until 1988. Admission fees as a factor in accessibility and outreach can’t be overstated; current admission fees put a museum visit out of the reach of many families and much of the population targeted by current outreach efforts. It’s unlikely that the gafs and omissions experienced during 9 Artists / 9 Spaces would be repeated; institutions, not only arts organizations, today are far more cautious, the threat of lawsuits and reprisals effectively censoring any potential or perceived transgressions. In the late sixties, according to Martin Friedman, “it would never occur to anybody to hold back.” The political atmosphere during the Vietnam War was explosive and revolutionary, but earnest, contrasting substantially with the cynicism and irony characterizing the present. The audience of the sixties was open with expectation.

It wasn’t about the audience. The focus, under Director Martin Friedman’s direction, was absolutely clear: the artist was paramount. Notable in all of my interviews was the sense that there was absolutely no intention, or even interest, in expanding audiences. The audience was respected, not cultivated; challenged rather than nurtured. “Certainly,” stressed Dean Swanson, “in a contemporary art museum it is primarily about the artist.” The triad of artist, arts organization and audience is not equilateral; the artist, in the act of creation, is making the fundamental connection.

This essay was part of a website (archived here) commissioned by The San Francisco Foundation in 2008.

Related Piece:

LACMA UNFRAMED June 3, 2015, Robert Whitman’s Communications Projects, A Personal History

Recently, artist Robert Whitman visited the Art + Technology Lab to reflect on his long career. Hosting an evening devoted to Whitman’s work was an obvious choice for the Lab’s conversation series; spanning more than four decades, his projects have involved telex, satellite transmission, live broadcasts, pay telephones and directed walks, and offer a foundational perspective for artists working with technology.

Whitman was a participant in LACMA’s Art and Technology program in the late 60s, and it was a pleasure to welcome him back on the eve of his 80th birthday to discuss the poetics of simple description, directed walks, and the role of the audience as participants. He also showed his latest work, SWIM, a work commissioned to be accessible to the blind, and performed at Montclair University in New Jersey last March. In the piece, the swooshing of washing machines gives way to the “woosh-woosh” of an onstage echocardiogram followed by magnetic knocks from an MRI. There is a video of his granddaughter performing, first at age six, and then again at age 10, a song she wrote titled “Echo.”

I had a distant personal connection to one of Whitman’s projects as my mother, Suzanne Weil, was the Coordinator for Performing Arts at Walker Art Center in Minneapolis from 1968 to 1976. Her programming brought experimental music and performance to the Twin Cities with extended residencies for Philip Glass, Mabou Mines, Twyla Tharp, and several of the artists involved in the original E.A.T. (Experiments in Art and Technology) program, including John Cage, David Tudor, Robert Whitman, Yvonne Rainer, and Trisha Brown. I was not in town for all of these events, and I heard about many of them by telephone. I remember her describing the Robert Whitman piece,NEWS. She’d arranged for him to do a live broadcast from the local public radio station while the audience followed a route through the city, stopping at designated phone booths to phone in simple descriptions of their surroundings.

A few years ago, when I was involved with works that included mobile phones and city gaming, my mother brought up the Whitman piece, this time recalling that their path that day in 1972 had serendipitously matched that of a wedding party occurring that afternoon so that the phoned-in descriptions broadcast live from the radio station chronicled the progression of the unsuspecting bride and groom as they entered and left various venues. I was struck by the significance of NEWS as a precursor to many of the themes that interest artists and game designers today, particularly those who work with mobile and locative media.

Whitman was not content to leave NEWS to the history books; as mobile phones gained the capacity to upload and stream live video, the piece was reprised as Local Report and performed, with variations including live satellite streaming, around the world. Together, NEWS and the many variations of Local Report form a corpus of works known as the Telecommunications Projects.

Having Robert Whitman in the Lab brought my participation in the original NEWS performance full circle; echoes of my mother’s description of the performance in 1972 overlaid with the discussion in 2015.