Forecast Public Art / Public Art Review • Going with the Flow

Source: Going with the Flow – Los Angeles’s first biennal uses public art as a catalyst to engage citizens in a conversation about water, Angela D’avignon. Forecast Public Art / Public Art Review, February 13, 2017

LOS ANGELES – On a sweltering Saturday afternoon in July, I joined a handful of other spectators in crouching at the paved edge of the Los Angeles River. “Water has memory,” a voice said and echoed over the gentle stream where four women dressed in shades of gray stood knee-deep in the water, gesturing toward the sky.

The performance, called A Water Dream, was presented by Women’s Center for Creative Work and was among the first of many, happening simultaneously all along the river on the inaugural day of CURRENT:LA Water, Los Angeles’s month-long public art biennial, the first of its kind.

It was a confluence between the Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs (DCA) Public Art Division and Bloomberg Philanthropies’ Public Art Challenge, which in June awarded grants to four cities to develop dynamic public art projects that address critical urban issues. CURRENT:LA Water was the first iteration of what are planned to be regular, issue-driven biennials in Los Angeles. The initial theme of water was especially pertinent, as the region has experienced record drought for the last four years with Los Angeles making ongoing, citywide efforts to reduce its water usage and become more water independent.

Participation as Activation

As a massive but expertly organized collaboration between the city, artists, and supporting organizations, the biennial used a celebration of Los Angeles and its relationship to water as a strategy to engage with the public.

At the outset, a team of four LA-based curators worked with 16 artists—10 individuals and three teams of 2—to envision and engineer 15 temporary, site-specific works driven by socially engaged practices. Spread throughout Los Angeles County at water-significant locations like the Sepulveda Basin and Echo Park Lake, each artist considered their respective sites in relation to water. The ephemeral nature of the art allowed each site to become a gathering place for education and dialogue. In addition to the 15 sites, a volunteer and information center called the HUB, located at the William Mulholland Memorial, served as the nexus for the biennial, providing resource materials as well hosting panel talks and workshops.

Performance was another key strategy to activating each space and much of the work could not exist without the presence of its practitioners. Art duo and noise band Lucky Dragons invited the public to watch their open rehearsals for the first three weeks of the biennial, which resulted in their final performance, The Spreading Ground, featuring a chorus ensemble of unamplified voices that stretched the two-mile length of the Hansen Dam. Like evaporating water, the impermanence of these experimental performances pointed back to the location itself, highlighting the physical terrain in which they took place.

A major strength was in the programming, supported by a calendar of events named ConCURRENT, which relied on the public’s participation, with something scheduled for every day of the month-long biennial. These events demonstrated a wide range of scope: educational, cultural, and communal. They included water conservation workshops, tea ceremonies using purified water from the river, and KPARK, a day-long event where artist-run radio station KCHUNG broadcasted live from different participating parks. Social media was key in connecting the public and tracking engagement, with hashtag #CURRENTLA linking hundreds of Instagram images snapped all over Los Angeles County.

Directly addressing the dense urban sprawl of Los Angeles, the biennial not only offered something local for each neighborhood but also provided an opportunity to explore other pockets of L.A. According to Kate D. Levin, who oversees the Bloomberg Philanthropies Arts program, this social cohesion was part of the goal. “The conversations that take place in selecting sites, the conversations that take place with artists installing their work, and the conversations that take place among people who are visiting these works are all part of the unique kind of energy that we believe public art projects bring to cities,” said Levin.

In traveling from spot to spot, participants discovered a connected and integrated city while learning something new about the particular area where each work was located.

The Importance of Place

The story of Los Angeles is the story of water. “We’re here in this landscape shaped by the power of water—both in its presence and by its absence,” said Jon Christensen, journalist-in-residence in the Institute of the Environment and Sustainability at UCLA and moderator of “Water as Power,” one of three panel discussions held weekly at the HUB.

That Los Angeles is a desert is a myth, as it was once home to natural floodplains that in the 1930s led to a series of devastating and deadly floods. The Los Angeles River was then paved over and channelized, used as a massive storm drain system rather than a critical natural resource. If you were to ask, most Angelenos are not aware a river runs through their city, let alone know anything of its history. The site of the river is important in determining a sense of place in Los Angeles, and highlighting the physicality of the area points to how citizens can relate to the terrain in which they live.

Making Los Angeles more water independent has long been a concern of Mayor Eric Garcetti’s office, with a special focus on revitalizing the Los Angeles River. In line with these efforts, the biennial offered a specific glimpse into its already vibrant history—one that largely goes unseen.

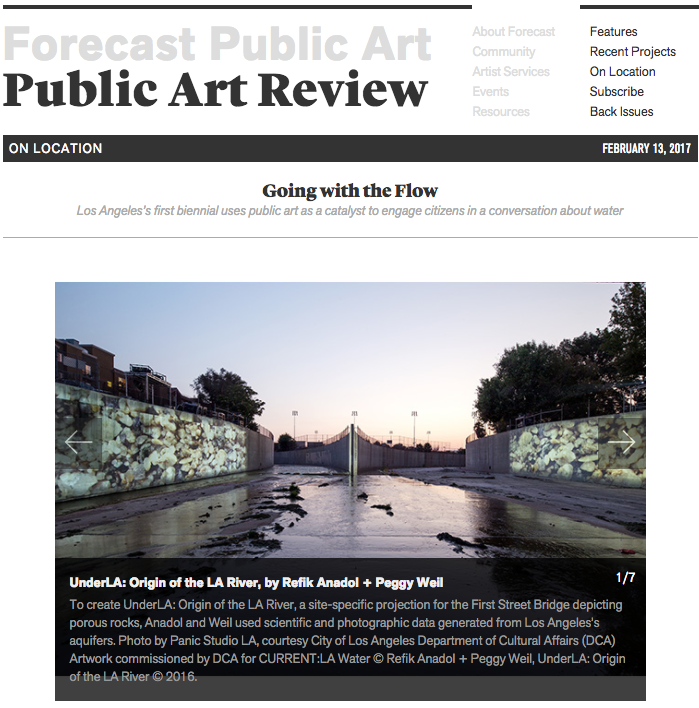

For example, Refik Anadol and Peggy Weil’s video work UnderLA projected photographic images of the sedimentary layers beneath the city’s aquifers onto the concrete banks of the river near the First Street Bridge, revealing a geological context to the river’s origins. Similarly, Kerry Tribe’s film Exquisite Corpse, which was screened outdoors at Sunnynook River Park, captures one mile of the river per minute from Canoga Falls to the Glendale Narrows, to the shore of Long Beach. Each shot reveals the life of the river and its inhabitants, including cats, homeowners, historic graffiti-writers, firefighters, and skateboarders, as well as the landscape itself.

While many of the works were more conceptual than formal, some were sculptural and involved many hands to make them happen. Teresa Margolles’s considerable concrete structure La Sombra (The Shade) at Echo Park Lake is a monument to lives lost in Los Angeles. The artist commissioned a team to wash the sites of 100 individual murders throughout the city—of 975 committed between January 1, 2015 and July 1, 2016—then retrieved and used that water and the material it absorbed to mix the cement that was used to build her sculpture. The result is an enormous object that is both ominous and inviting, offering respite from the sun. Video documentation of the process was screened at local businesses around the Echo Park area, including a barber shop and a thrift store. Community-wide inclusion and representation were key.

Ambitious and far-reaching, CURRENT:LA Water aimed to catalyze long-term engagement within the city and among its residents. “It’s about the excitement of the individual works, then seeing them put together as a whole, and hoping that Angelenos discover something about themselves, something about their city, and something about each other in the course of experiencing this particular project,” said Levin.

The dialogues that began at the biennial are a means for continued civic engagement, as well as an innovative way for the public to learn about the city’s history and, together, imagine its future.